Inversion of Control

Overview

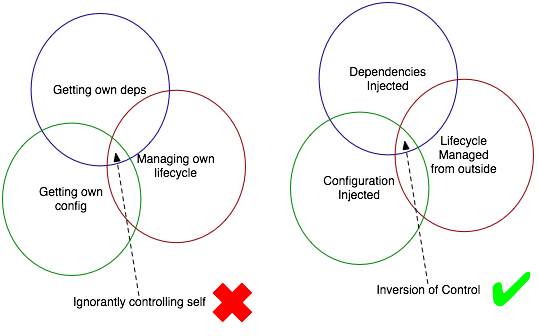

Inversion of Control (IoC) is a design pattern that addresses a component’s dependency resolution, configuration and lifecycle. It suggests that the control of those three should not be the concern of the component itself. Thus it is inverted back. Note to confuse things slightly, IoC is also relevant to simple classes, not just components, but we will refer to components throughout this text. The most significant aspect to IoC is dependency resolution and most of the discussion surrounding IoC dwells solely on that. Dependency mis-management is acknowledged to be the biggest problem that IoC is trying to solve.

Types of IoC

There are many types of IoC, but we’ll concentrate on the type of IoC that PicoContainer introduced - Constructor Injection .

IoC History

Some detail about the history of Inversion of Control - IoC History

Component Dependencies

It generally favors loose coupling between components. Loose coupling in turn favours:

- More reusable classes

- Classes that are easier to test

- Systems that are easier to assemble and configure

Explanation

Simply put, a component designed according to IoC does not go off and get other components that it needs in order to do its job. It instead declares these dependencies, and the container supplies them. Thus the name IoC/DIP/Hollywood Principle. The control of the dependencies for a given component is inverted. It is no longer the component itself that establishes its own dependencies, but something on the outside. That something could be a container like PicoContainer, but could easily be normal code instantiating the component in an embedded sense.

Examples

Here is the simplest possible IoC component :

public interface Orange {

// methods

}

public class AppleImpl implements Apple {

private Orange orange;

public AppleImpl(Orange orange) {

this.orange = orange;

}

// other methods

}

Here are some common smells that should lead you to refactor to IoC :

public class AppleImpl implements Apple{

private Orange orange;

public Apple() {

this.orange = new OrangeImpl();

}

// other methods

}

The problem is that you are tied to the OrangleImpl implementation for provision of Orange services. Simply put, the above apple cannot be a (configurable) component. It’s an application. All hard coded. Not reusable. It is going to be very difficult to have multiple instances in the same classloader with different assembly.

Here are some other smells along the same line :

public class AppleImpl implements Apple {

private static Orange orange = OrangeFactory.getOrange();

public Apple() { }

// other methods

}

Component Configuration

Sometimes we see configuration like so …

public class BigFatComponent {

String config01;

String config02;

public BigFatComponent() {

ResourceFactory resources = new ResourceFactory(new File("mycomp.properties"));

config01 = resources.get("config01");

config02 = resources.get("config02");

}

// other methods

}

In the IoC world, it might be better to see the following for simple component designs :

public class BigFatComponent {

String config01;

String config02;

public BigFatComponent(String config01, String config02) {

this.config01 = config01;

this.config02 = config02;

}

// other methods

}

Or this for more complex ones, or ones designed to be more open to reimplementation ..

public interface BigFatComponentConfig {

String getConfig01();

String getConfig02();

}

public class BigFatComponent {

String config01;

String config02;

public BigFatComponent(BigFatComponentConfig config) {

this.config01 = config.getConfig01();

this.config02 = config.getConfig02();

}

// other methods

}

With the latter design there could be many different implementations of BigFatComponentConfig. Implementations such as:

- Hard coded (a default impl)

- Implementations that take config from an XML document (file, URL based or inlined in using class)

- Properties File.

It is the deployer’s, embeddor’s or container maker’s choice on which to use.

Component Lifecycle

Simply put, the lifecycle of a component is what happens to it in a controlled sense after it has been instantiated. Say a component has to start threads, do some timed activity or listen on a socket. The component, if not IoC, might do its start in its contructor. Better would be to honor some start/stop functionality from an interface, and have the container or embeddor manage the starting and stopping when they feel it is appropriate:

public class SomeDaemonComponent implements Startable { public void start() { // listen or whatever } public void stop() { } // other methods }h3. Notes

The lifecycle interfaces for PicoContainer are the only characterising API elements for a component. If Startable was in the JDK, there would be no need for this. Sadly, it also menas that every framework team has to write their own Startable interface.

The vast majority of components do not require lifecycle functionality, and thus don’t have to implement anything.

IoC Exceptions

Of course, in all of these discussions, it is important to point out that logging is a common exception to the IoC rule. Apache has two static logging frameworks that are in common use: Commons-Logging and Log4J. Neither of these is designed along IoC lines. Their typical use is static accessed whenever it is felt appropriate in an application. Whilst static logging is common, the PicoContainer team do not recommend that developers of reusable components mandate a logging choice. We suggest instead that a Monitor component interface is created and default adapters are provided to a number of the logging frameworks are provided.

Overview

IoC Types - Family Tree

In recent years different approaches have emerged to deliver an IoC vision. Latter types, as part of a ‘LightWeight’ agenda have concentrated on simplicity and transparency.

Devised in London at the ThoughtWorks office in December of 2003; Present at the”Dependency Injection”meeting were Paul Hammant, Aslak Hellesoy, Jon Tirsen, Rod Johnson (Lead Developer of the Spring Framework), Mike Royle, Stacy Curl, Marcos Tarruela and Martin Fowler (electronically).

Inversion of Control

- Dependency Injection* Constructor Dependency Injection (CDI)

Examples: PicoContainer, Spring Framework, (not in EJB 3.x sadly), Guice with Annotations

- Setter Dependency Injection

Examples: Spring Framework, PicoContainer, EJB 3.0&Guice with Annotations

- Interface Driven Setter Dependency Injection

Examples: XWork, WebWork 2

- Field Dependency Injection

Examples: Plexus, PicoContainer&Guice with Annotations.

- Dependency Lookup* Pull approach (registry concept)

Examples: EJB 2.x that leverages JNDI, Servlets that leverage JNDI

- Contextualized Dependency Lookup - AKA Push approach

Examples: Servlets that leverage ServletContext, Apache’s Avalon, OSGi, Keel, Loom (they use Avalon) See also Constructor Injection , Setter Injection for more information.

Note Field Injection was categorised but there was was really no interest it until the EJB3.0 specification rolled out. Getter Injection flourished for a while, but did not take and was never supported by the PicoContainer team.

Examples of Common Types

Constructor Dependency Injection

This is where a dependency is handed into a component via its constructor :

public interface Orange {

// methods

}

public class AppleImpl implements Apple {

private Orange orange;

public AppleImpl(Orange orange) {

this.orange = orange;

}

// other methods

}

Setter Dependency Injection

This is where dependencies are injected into a component via setters :

public interface Orange {

// methods

}

public class AppleImpl implements Apple {

private Orange orange;

public void setOrange(Orange orange) {

this.orange = orange;

}

// other methods

}

Contextualized Dependency Lookup (Push Approach)

This is where dependencies are looked up from a container that is managing the component :

public interface Orange {

// methods

}

public class AppleImpl implements Apple, DependencyProvision {

private Orange orange;

public void doDependencyLookup(DependencyProvider dp) throws DependencyLookupExcpetion{

this.orange = (Orange) dp.lookup("Orange");

}

// other methods

}

Terms: Service, Component&Class

Component is the correct name for things managed in an IoC sense. However very small ordinary classes are manageable using IoC tricks, though this is for the very brave or extremists

A component many have dependencies on others. Thus dependency is the term we prefer to describe the needs of a component.

Service as a term is very popular presently. We think ‘Service’ dictates marshaling and remoteness. Think of Web Service, Database service, Mail service. All of these have a concept of adaptation and transport. Typically a language neutral form for a request is passed over the wire. In the case of the Web Service method requests are marshaled to SOAP XML and forward to a suitable HTTP server for processing. Most of the time an application coder is hidden from the client/server and marshaling ugliness by a toolkit or API.

Dependency Injection versus Contextualized Lookup

Dependency Injection is non-invasive. Typically this means that components can be used without a container or a framework. If you ignore life cycle, there is no import requirements from an applicable framework.

Contextualized Dependency Lookup is invasive. Typically this means components must be used inside a container or with a framework, and requires the component coder to import classes from the applicable framework jar.

Note that Apache’s Avalon OSGi are not Dependency Injection types of IoC, they are Contextualized Dependency Lookup.

Ultimately, the contextualized lookup designs are not recommended at all.

What’s wrong with JNDI ?

With plain JNDI, lookup can be done in a classes’ static initialiser, in the constuctor or any method including the finaliser. Thus there is no control (refer C of IoC). With JNDI used under EJB control, and concerning only components looked up from that bean’s sisters (implicitly under the same container’s control), the specification indicates that the JNDI lookup should only happen at a certain moment in the startup of an EJB application, and only from a set of beans declared in ejb-jar.xml. Hence, for EJB containers, the control element should be back. Should, of course, means that many bean containers have no clue as to when lookups are actually being done, and apps work by accident of deployment. Allowing it for static is truly evil. It means that a container could merely be looking at classes with reflection in some early setup state, and the bean could be going off and availing of remote and local services and components. Thus depending whether JNDI is being used in an Enterprise Java Bean or in a POJO, it is either an example of IoC or not.

Related Pages

- Contextualized Lookup - Avalon Framework

- IoC History

- Dependency Injection

- Constructor Injection

- Setter Injection